Paragraph. Zur Bearbeitung hier klicken.

Paragraph. Zur Bearbeitung hier klicken.

Posted by Carlos This is an unusually personal blog. In addition to the millions who have succumbed to this deadly virus, the world over has been struggling with COVID-19 in a multitude of ways for more than a year now. What stands out is when we help our fellow human beings. Of course, there are the applauded yet overworked and underpaid heroes in our healthcare systems; however, even when not on the frontlines, everyone can make a significant difference within their own remit. Located in Berlin’s western district of Charlottenburg and priding itself in being ‘the hotel with a difference’, Pension Peters is a case in point. In what is now a decade of working as a guide, I have been fortunate to travel Europe and to meet a kaleidoscope of characters with one thing in common: a genuine openness to strangers. This comes as little of a surprise in the case of Pension Peters, given Johanna and Olga Steiner’s Swedish and Czech heritage. The two sisters own and run the hotel in its second generation, with an affinity for art and sustainability. They take a genuine interest in their guests, whose check-ins resemble less a formal procdure than they do a conversation among old friends who have not seen each other for years. The hotel supports local, still unknown artists by adorning their corridors with paintings and hosting an exhibition at least once a year. The Steiner sisters share their knowledge and passion for Berlin as well as any guide could. It is not least for this reason that the Hotel Pension Peters has worked with Rick Steves even before his fame reached dizzying heights. Of course, the Hotel Pension Peters has been affected dramatically by the pandemic. With tourism being one of Berlin’s most important industries, the economic ripple effects of Corona have been real and tangible. Over a hundred fellow guides, many of whom are friends, have lost their livelihoods. In the absence of tourists, small businesses, such as hotels, bars and restaurants have been struggling to stay afloat. This backdrop makes the story I was able to witness particularly moving. Johanna and Olga had been receiving and looking after an ailing guest since the beginning of 2019. Working in Switzerland, this guest repeatedly had contracted cancer and sought treatment in Berlin each time. Staying at the Pension Peters placed her within walking distance of her oncologist and close to her son, who lived nearby. In addition, she got to know the Steiner family well and enjoyed long conversations about history, theatre and life in general with the sisters’ mother Annika. Spring 2020 saw difficult times descend upon this guest. Until then, it had appeared as though she would remain cancer-free, having undergone a mastectomy a few years before and passing all check-ups with flying colours ever since. She had looked forward to returning to her home on the other side of the Atlantic and dividing her retirement between there and Berlin. After sustaining a fall, her visit to the doctor bore worse news than a broken sternum: she had contracted breast cancer for a fourth time; and this time it was incurable. The Steiner sisters stepped up to help their guest and her family in this time of need. They already had struck up a friendship with her from the outset. They now allocated her a room on the ground floor, which was otherwise sealed off to guests, and gave her access to kitchen as well as the usual facilities hotel guests enjoy. They provided her son with a spare key so that he could visit and look after her on a regular basis. Soon the guest suffered from further complications, notably liquid filling her lungs. This required her to spend several stints in about half a dozen of Berlin’s hospitals over the summer. In this time, the Steiners maintained her room and supported the family all the same. When she was released from hospital and returned to the hotel, they served as the “eyes and ears” of her son while he worked as school teacher during the day. The hotel became a temporary caretaking station in which the guest’s son could act as a de facto nurse for as long as the situation required. Alas the situation was tenable only for so long. The guest’s condition worsened. Metastases had spread from the lungs to the skin and chemotherapy was added to an already strenuous treatment. The concern was now a threefold one: she could succumb either to her illness, her physically frail condition or to Corona. The availability of a suitable nursing home in November provided a sigh of relief. Being ensconced promised to save her from all three lethal threats. Medical transportation to and from the oncologist for chemotherapy could be arranged for as well. However, literally every body has its limits. By the beginning of December, the patient had undergone nine of ten sessions of chemotherapy. Her final appointment had to be postponed as her condition worsened. After appearing to be on the mend from this setback, she took both the nursing staff and her family by surprise. She passed away peacefully in her sleep on a Saturday afternoon. In the aftermath, the Pension Peters remained true to itself. Johanna and Olga allowed their late guest’s son to retain her belongings in her room for as long as he needed. They initially refused to accept anything more than a token sum that would amount to less than an average monthly rent in Berlin in exchange for almost half a year of support. It had been their guest’s wish that they accept a multiple of that and so they had no other reasonable option but to take more. As a guide, I often hear both from guests and operators how important it is to support local businesses. We tend to romanticise their worth and politicians across the Atlantic have an affinity for putting them on a pedestal on campaign trails. Life’s stories and realities lend more strength to this position than any romanticism ever could. As this terrible year draws to a close, a good new year’s resolution would be to make a start with the Hotel Pension Peters and its genuinely humanely beautiful owners, once it is safe to travel again.

1 Comment

The original (cool) rocket slide in Rocketship Park. Photo credit patch.com The original (cool) rocket slide in Rocketship Park. Photo credit patch.com Posted by Torben Traveling with children is hard work. Everything takes longer, everything is more stressful. And that's before you figure out what you're going to do with them when you get there. Berlin offers plenty of options, from Legoland to two big zoos, but you don't have to fly to Germany to see exotic animals or admire elaborate lego creations. Berlin does, however, hold one attraction that's become hard to find in the US: cool playgrounds. A couple of years ago, while back on suburban Long Island where I grew up, I happened upon the local public playground that it had been such a treat to visit as a kid, the ambitiously named Rocketship Park (located in the village of Port Jefferson). The experience was devastating. The playground had been turned into a padded abomination of boring, a place where it was both impossible to hurt yourself and impossible to have fun. The Rocketship Park of my childhood boasted a huge rocketship you could climb up with a slide about halfway up to the top. The new Rocketship Park also has a rocket with a slide (two slides, actually), but it's small and stupid. Then there is some sort of pirate ship construction, which could be cool if the nets and rope ladders hanging down extended more than two feet off the ground. Said ground, by the way, is light blue composite rubber and looks like it was intended for the “time out” room at a mental hospital. Now, first impressions can be deceiving: based on photographic evidence, I'm forced to concede that maybe the original rocketship was not quite as big as I remember it. Also, a rocketship? According to Wikipedia, Cold War-era playground equipment was “intended to foster children's curiosity and excitement about the Space Race” and a means whereby “nuclear weapons were made intelligible in, and transposable to, a domestic context.” This is true, by the way, for both the West and Eastern Bloc countries. So much for the unalloyed innocence of my childhood. And that pirate ship thing is apparently wheelchair-accessible, not the worst thing in a world where, at most playgrounds, the wheelchair-bound are entirely excluded. Those qualifications notwithstanding, however, I can say with confidence that Berlin has the superior playground scene. First of all, playgrounds here are plentiful. Berlin has 1,858 of them – that's more than three times as many as Paris. Second, many of them are relatively new, and an effort is made at upkeep (in the current fiscal year, Berlin is spending 32 million Euros to fix up and improve 101 playgrounds as well as 38 day care centers). Third and most importantly, many of them are fun! As Anna Winger has written in the New York Times: “Guided by what most German parents consider a healthy chance for children to mitigate risk in the interest of developing selbstständigkeit, self-sufficiency — or what some American parents might deem a total lack of concern for child safety — playgrounds here are physically challenging and ambitious in design. […] Public space in Germany is not held hostage by liability lawsuits; Berlin playgrounds are not designed by lawyers. Thus they offer an opportunity for exploration that is, well — playful. It’s enough to make some of my American visitors, many who admit to being helicopter parents (one friend giddily describes herself as a Black Hawk) — weak at the knees.” In this spirit, many Berlin playgrounds, right in the middle, will have a big, friggin' rock! Also, many of the attractions are hard to use: there's no ramp or steps or ladder leading up to the top of the slide, instead you have to climb and crawl, balance and strain for the pay-off. (And things can go wrong. One of the playground staples that I remember most fondly from childhood visits to Germany is the zipline: you pull the attached rope to the top of a ramp, wrap yourself around it (there's a little disc at the bottom that functions as a miniature seat), hold on tight, and slide on a steel cable until you're stopped abruptly, inertia yanking you into the air. I was convinced my three-year-old son would love this as much as I did, but miscalculated his speed. Happily, my son held on tight and was not launched into the abyss. Still, he refused to go near the thing for many months after.) German playgrounds, in short, are designed to encourage physical activities that entail some level of risk. This is based on the assumption that risk-taking is necessary for the development of certain motor skills – and that acquiring these motor skills ultimately reduces the risk of accident and injury. And kids need to be cajoled into physical activity: a longterm study of German children has found that the motor skills of kids today are 10% weaker than in the 1970s. Of course, lack of exercise among children is not a uniquely German phenomenon. But Germany compares poorly in this regard with the United States. A recent WHO study found that, globally, 85% of girls and 78% of boys do not get the one hour of physical activity per day the WHO recommends. Germany does worse than the global average, with 88% of girls and 80% of boys getting too little exercise. The figures for the United States, on the other hand, are 81% for girls, 64% for boys. Moreover, apart from health concerns, the need for public playgrounds is more widespread in densely populated Germany. Even in suburbs, exurbs, and rural areas, backyards are tiny compared with the US. And in a country with a low birth rate that is not very child-friendly, playgrounds are a place where kids are allowed to play without the risk of reproach. Playgrounds, in other words, play a complex social role in Germany (and especially in a big city like Berlin). The development of motor skills is one thing, but it's not sufficient for playgrounds to consist of glorified exercise equipment: play and exercise may overlap, but they're not the same. Thus Berlin's playgrounds sport houses and boats and airplanes you can climb onto or into and that are great for role-playing. They have swings that accommodate more that one child so that kids not used to sharing with a brother or sister can learn to play together. Many playgrounds have water features, where the kids themselves pump the water and are in control of where it flows: it can be dammed and rerouted or power little mills. Ultimately, though, the water ends up on the sandy ground to produce another great playground attraction: mud. The sandbox, of course, distinguishes itself from other playground staples (slide, swing, see-saw) in that there is no one “right” way to play with sand. This, experts note, should be the ambition of playgrounds: to foster creativity, to encourage children to decide for themselves how to play, rather than having a “proper” use dictated to them. This idea is not new. As early as the 1930s, the designer Isamo Noguchi tried to convince New York City Parks Commissioner Robert Moses to build Play Mountain, a playground without any equipment where the landscaping alone would afford opportunities for play.

It seems that, generally, the period from the 1940s through the 1970s was a time of rich experimentation when it came to playgrounds. In 1943, in the middle of World War II, the first “junk playground” was established on the outskirts of Copenhagen. Kids built their own equipment out of junkyard materials with little to no oversight. The so-called skrammellegepladsen was the forerunner of “adventure playgrounds.” These were only established in Germany in the 1970s, in part as an outgrowth of the social progressivism we associate with 1968. But for all the creativity and joyful experimentation that went into the design of playgrounds in the decades following World War II, their widespread establishment was a double-edged sword. In a way, they were a manifestation of what one playground designer has called (and the term is of course highly problematic) the “ghettoization” of children. In Germany, everyone is familiar with stories of their grandparents playing amidst the rubble of bombed out cities. Designated playgrounds, happily, replaced the rubble. But then these playgrounds came to be seen not only as a place to play, but as the only place to play. Some theorists have suggested that the goal should be to get rid of playgrounds altogether. Instead, the city as a whole should become so child-friendly as to make playgrounds unnecessary. For all my dismay at the transformation of the Rocketship Park of my childhood, I was not dependent on public playgrounds on suburban Long Island. Instead, we played in the backyards and the woods of our neighborhood, and we were restricted in our movement only insofar as we had to be home in time for dinner. Or else. Which brings us to the great enemy of avantgarde playground designers: parents. In Berlin, it is not unusual for parents to outnumber the children at playgrounds. They are places where moms and dads can meet and have a cup of coffee (in Covid times especially), and where the children (ideally) will entertain themselves. Contemporary playgrounds aren't, as they were in the past, just for the working-class – a place kids could hang out while their parents were at work. All children go to the playground, and they are always under the observation of their parents. By the 1980s, playground experimentation had ended. Many that were especially creative were shut down out of safety or (in the US) liability concerns. And playgrounds were built in such a way that parents could always overlook their entire expanse. One of the cutting-edge playgrounds the architect Richard Dattner designed in the 1970s for New York featured a low wall to at least symbolically separate parents from children. Now kids (literally) had no place to hide. I think some of what was lost in the last several decades has returned to the playgrounds of Berlin. Earth mounds to hide behind, tubes to crawl through, climbing structures to jump (or fall) off of, mud to ruin your clothes in: it's a child's dream, if a parent's nightmare. Still, I'm grateful for the proliferation of playgrounds in the city, and for their variety. To see your kid have fun – well, skinned knees and muddy jeans seem like a small price to pay. Posted by Torben  The groundbreaking ceremony for the Hermann-Göring-Kaserne ca. 1935. Göring is in the center looking left. Photo credit Michael Kemp, distributed under CC BY-SA 4.0 license. The groundbreaking ceremony for the Hermann-Göring-Kaserne ca. 1935. Göring is in the center looking left. Photo credit Michael Kemp, distributed under CC BY-SA 4.0 license. When I go running through the Rehberge, a large and understatedly beautiful park near my apartment, I often pass swiftly marching soldiers wearing camouflage uniforms and lugging military packs. It is evident they've been trained to be courteous: they generally say hello as I pass, which is decidedly not the Berlin thing to do. I assume they come from the military barracks that border the park, the largest in Berlin and home to the guard battalion that performs military honors for state guests. The base is named for the resistance fighter Julius Leber. It used to be named for Hermann Göring. The origins of the facility date back to the late 19th century, when the Luftschifferbataillon, the “airshipmen battalion,” considered to be the first regular air force unit in the world, was established and based here. Following Germany's defeat in World War I, the unit was disbanded – the Treaty of Versailles prohibited Germany from having an air force. Instead the barracks were used by the police. In 1936, however, Göring, whom Hitler had appointed as air minister in 1933 and who took charge of the Luftwaffe after it was established in contravention of the Versailles treaty in 1935, began construction of a sprawling new barracks complex on the site. After World War II the facility became the headquarters of the French occupying forces in Berlin and was expanded to form the Quartier Napoléon that included a Catholic church, a house of culture, a movie theater, and a swimming pool. In 1948 the French military, with the help of American specialists and locals, constructed an airfield just across the road from the barracks. (The site they chose had been used to test airships before World War I and rockets in the 1930s. The scientists involved in the latter endeavor include Rudolf Nebel and Wernher von Braun.) A first runway was built in just 90 days. Time was of the essence. The Soviets had blockaded West Berlin and the only way to get food and supplies into the city was by air. On November 5th a Douglas C-54 Skymaster carrying eight tons of cheese became the first plane to land at what would become Tegel Airport. With reunification Germany regained its sovereignty and Berlin, previously under Allied administration, became a part of the Federal Republic of Germany (technically, West Berlin had not been a part of West Germany). The French military left Berlin and the German military, the Bundeswehr, took over the Quartier Napoléon. In early 1995, on the 50th anniversary of Julius Leber's death, it was renamed. Why name a military base after Julius Leber? To be sure he had been a decorated soldier in World War I. But his military career was cut short in 1920 when, as a lieutenant, he sided with the democratic Weimar Republic against right-wing insurgents during the so-called Kapp Putsch. This was considered an unforgivable act by the largely pro-putsch officers' corps. Leber became a journalist and later a Social Democratic member of the Reichstag. Shortly after Hitler assumed power Leber and two fellow activists were involved in an altercation with a group of Nazi SA men in which one of Leber's companions killed a storm trooper in self defense. Leber was arrested, imprisoned for 20 months, then sent to Esterwegen and Sachsenhausen concentration camps. In 1937 Leber was released and became involved in the resistance against the Nazi regime. A shed in the Berlin district of Schöneberg from which he sold coal was a conspiratorial meeting place. Leber's contacts extended far beyond his social democratic milieu. He was part of the plot to assassinate Hitler led by Colonel Claus Schenk Graf von Stauffenberg (to whom he grew quite close) and was designated as Germany's minister of the interior if the plot succeeded. In an effort to form as broad a coalition against the regime as possible, Leber reached out to members of the communist resistance, but was betrayed by a Gestapo mole. He was arrested shortly before Stauffenberg's failed assassination attempt of July 20th 1944, made the subject of a sham trial, and executed on January 5th 1945. Leber, it is clear, is very much worthy of remembrance, but not because he was a famous war hero or a successful general. Instead we honor Leber because he gave his life fighting against an evil regime. Specifically, Leber supported the coup attempt of an army colonel who tried to kill the so-called Führer to whom he, Stauffenberg, had personally sworn an oath of allegiance. From 1934 onwards, German soldiers would “...swear to God this holy oath that I shall render unconditional obedience to the Leader of the German Reich and people, Adolf Hitler, supreme commander of the armed forces, and that as a brave soldier I shall at all times be prepared to give my life for this oath." Stauffenberg broke that oath, as of course he should have: it is strange for us today to observe how Stauffenberg and others wrestled with the morality of breaking an oath made to such an obviously monstrous figure. But the question for a military organization like the Bundeswehr is: should it base its sense of tradition on someone who broke his military oath, who did not follow orders, who attempted a coup? Is that dangerous for discipline and for the smooth functioning of a military?

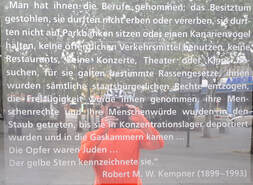

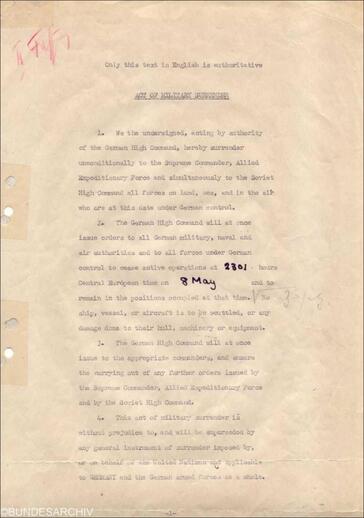

Germany's answer is clear: the military resistance to Hitler is absolutely integral to the Bundeswehr's identity and has been since its establishment in the mid-1950s. It is no accident that the Berlin branch of the German defense ministry (the main headquarters remains in Bonn) is housed in the Bendlerblock where Stauffenberg had his office. It has become a ritual for German soldiers to pledge their oath to serve the Federal Republic in public on every July 20th, the anniversary of Stauffenberg's failed coup attempt. Often the pledge is held in the courtyard of the Bendlerblock, where Stauffenberg, along with three of his co-conspirators, was executed in the early hours of July 21st 1944. That the military resistance to the Nazi regime is so prominently remembered by the Bundeswehr is by no means uncontroversial. Stauffenberg held the prejudices of many Germans of his time. He made odious antisemitic and anti-Slavic comments. He at first welcomed Hitler's coming to power. Other members of the military resistance were complicit in fighting a criminal war in the Soviet Union. Most (including Stauffenberg) were deeply opposed to democracy – in part because they thought that it was democracy that had enabled Hitler's rise. But then, who else is there to lend the Bundeswehr some sense of tradition? The Prussian officers who fought against Napoleon, perhaps – and we have barracks named for Scharnhorst and Gneisenau and Blücher, the heroes of the early 19th century. But that was long ago. And it is important to recognize that the acknowledgement of the military resistance to Hitler marked progress in the early years of the Federal Republic. These men who had been abhorred as traitors to their country were now being held up as models by the young West German democracy. The question is, seventy years on, do we still need them? Germany is a more mature democracy than it was in 1955. And we have a more sophisticated understanding of the protagonists of the military resistance. We are acutely aware of the chasm that lies between their vision for Germany and the democratic, open society that most of us aspire to today. We can admire the bravery of those who gave their lives to rid Germany of Hitler while also acknowledging their flaws and accepting that they cannot serve as unqualified role models. The military historian Sönke Neitzel has written that he does not think there will be barracks named for Stauffenberg in another twenty years. But barracks named for Julius Leber? He was a lieutenant who stood up to the putschists against democracy within his own ranks; a journalist and social democratic member of parliament who supported democracy against the many who sought to bring it down; a man sent to a concentration camp for his efforts and executed for trying to rid the world of the Nazi regime. The Bundeswehr could do a lot worse. And perhaps the notion that tradition is integral to the cohesion and functioning of a military is a little overstated anyway. Certainly many, many American soldiers coming out of Fort Bragg served with distinction in World War II and helped topple the Nazi German regime – a feat the German resistance was not nearly strong enough to accomplish. And the soldiers from Fort Bragg don't seem to have been slowed down by the fact that their base was named for someone who, by most accounts, was a “bumbler.” More importantly, until very recently it doesn't seem to have been of great concern that Confederate General Braxton Bragg fought against the very military that built and operates the fort named for him. As the chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Mark A. Milley, said of the Confederate officers for whom military installations in the South are named (there are ten in total): “It was an act of treason, at the time, against the Union, against the Stars and Stripes, against the U.S. Constitution. Those officers turned their back on their oath.” But that was only last month. For a long time the fact that Fort Bragg was named for a slaveholder who fought against the Union was considered unproblematic. For a long time the German Bundeswehr saw Colonel Stauffenberg as a role model who could help lead Germany into a democratic future. To be clear, the United States and Germany have distinct histories – and Germany's history is distinctly awful. It is in no way my intention to make any – necessarily false – equivalencies. My point has to to with the role of military tradition: one reason it took so long for Germany to get rid of the draft (it was only abandoned in 2012) was a deeply held worry that, without draftees, the army would no longer be a reflection German society as a whole. A healthy military – the argument goes – should share the values of the community it serves. And if that holds true, then perhaps the sense of tradition of the military is inseparable from the sense of tradition of the country. The impetus for the top ranks of the US military to take a “hard look” at renaming bases named for Confederate officers has less to do with those officers' turning their back on their oath, but the nature of the regime they turned their back on their oath for. It was the Black Lives Matter protests that prompted a reassessment of the various ways in which representatives of the slaveholding Confederacy are honored today, not only by the military but everywhere. I don't mind that debate about Germany's democratic values has prompted the Bundeswehr to consider taking Stauffenberg, who still has his place, down a peg or two. Concerns about whether the Bundeswehr has grown aloof from German society have not gone away. There have been several troubling scandals involving right-wing extremism within its ranks in recent years. I feel that the friendly greetings of the uniformed marchers in the park are meant to assuage those concerns. Of course not all extremist soldiers will have become extremists after joining the army. For the moment German society as a whole – and not just the Bundeswehr – consider Julius-Leber-Kaserne to be a good name for a military installation. I for one hope it stays that way. Mirror, Mirror on the Wall ... What the Spiegelwand Memorial Tells Us about Holocaust Remembrance5/29/2020  Posted by Carlos Foreign visitors on our tours of Berlin often praise Germany for commemorating the victims of National Socialism. While the Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe (the Holocaust Memorial) in the city-centre is a frequent stop, I only once had the opportunity to take a family to the Spiegelwand memorial in the southern neighbourhood of Steglitz. Spiegelwand literally means ‘mirrored wall’. It is also a testament to the local tensions that underlies Germany’s acknowledgement of the Holocaust or Shoah as a nation. Wolfgang Göschel, Joachim von Rosenberg and Hans-Norbert Burkert designed a very special memorial in the 1990s. Unveiled ten years before the Holocaust Memorial, the Spiegelwand is a 9 metre high and 3.5 metre wide set of glass plates. These bear the names, dates of birth and addresses of 1,723 Jews who were deported and murdered. This monument is informed by surviving deportation lists of Jews from Steglitz and nearby areas. In this way, the victims can be honoured as individuals with a name, a history and a home. This is expressed in a quote of Robert Kempner, a Jewish resident of Steglitz and later plaintiff at the Nuremberg Trials. It adorns the Spiegelwand and can be loosely translated as follows: "One took their jobs, stole their possessions, they were not permitted to inherit or bequeath, they were not allowed to sit on park benches or keep a canary bird, to use public transport, to visit any restaurants, any concerts, any theatres or any cinemas, certain racial laws were applied to them, all civic rights were withdrawn from them, the right of free movement was taken away from them, their human rights and their human dignity was kicked into the dust, until they were deported into the concentration camps and came into the gas chambers ... The victims were Jews ... The yellow star marked them". And yet there is an almost inherent ambivalence to the memorial. To be sure, its location on Hermann-Ehlers-Platz, a central meeting place and home to a poplar market in downtown Steglitz, is appropriate. The memorial effectively points to the building that once served as a synagogue; however, the Spiegelwand is not immediately visible, nor is the former synagogue, when coming to the square from the main street. From a purely solipsistic or self-centred perspective, it is impracticable to show this to visitors with limited time to see Berlin. The Spiegelwand is literally out of the way. This is a lens through which one can view the heated debates over the memorial that consumed the parliament of Steglitz for years. The conservative CDU, the (economically) liberal FDP and the rightwing Republicans of Germany held a majority and opposed the design of the Spiegelwand. Among the many reasons they laboured was the concern that owing to its size the memorial could be besmirched by Neo-Nazis. To someone reading about the topic in hindsight, this is somewhat odd. The German Republicans have been known for their hard right sympathies; were they, out of respect for the victims and their families, pleading guilty to potentially vandalising a Holocaust memorial? As the controversy assumed grotesque dimensions in which almost every inch was negotiated, Berlin’s Social Democratic Minister for Construction and Housing Wolfgang Nagel intervened. The reputation of Berlin had begun to suffer. Looking back, this debate is strange only at first sight. Germany was confronted with a number of challenges as a reunified society in the early 1990s. Two different forms of commemoration of the National Socialist past had to be reconciled; concentration camp memorials, especially those in the former East Germany, were now redesigned; Neo-Nazism was on the rise; debates about the national Holocaust Memorial were taking place; and a travelling exhibition about the crimes of the regular German Army or Wehrmacht, hitherto seen as an honourable counterpart to the murderous SS during the Second World War, was making the rounds. Bearing responsibility for the guilt of the parent generation arguably was particularly hard for conservative Germans. Social Democrats, Communists and others whose political, religious, cultural or sexual identity had a history of persecution under National Socialism had something to protest against when dealing with the Third Reich. By contrast, it had been conservative and self-styled independent politicians led by Chancellor Franz von Papen who had convinced President Paul von Hindenburg to appoint Adolf Hitler Chancellor on 30 January 1933. The democratic credentials of the military officers and civilians behind the failed coup of 20 July 1944 – and often celebrated in conservative circles – were being viewed critically by the 1990s. It was hard to avoid confronting the simple truth that there was no excuse for Hitler and genocide. This feeling of guilt can be less a question of political conviction than of an unfinished process. As a native German speaker, I have found myself conversing in two worlds when showing my beloved city to English speakers. On the one hand, customers eager to learn about the Third Reich and to understand what lessons can be drawn for their own present have emphasised what a role model Germany and its memorials are to the rest of the world. On the other, drivers have told me in German that they are enervated by foreign visitors just wanting to see Third Reich sites as though Germany had nothing more progressive to offer and the rest of the world nothing but contempt for Germans. The irony is tangible as the significance of commemoration is almost lost in translation. The ambivalence the Spiegelwand can remind us of is not without merit. This local memorial underlies the national intent behind the Holocaust Memorial: the German state is at pains to show that the Germany of today is a different one to the National Socialist state and that it unequivocally bears responsibility for those whom it had persecuted and murdered. This Germany which wishes to learn from its shameful past is the ideal I find visitors admiring. The existence of these memorials shows that as a society Germany has come a long way. The debates at both the political level and in day to day conversations reveal that there still is a road that lies ahead. Not only should it be embraced, but with hope and optimism as well. Posted by Torben  The officers' mess at the former military engineering school in Berlin-Karlshorst taken over by the Soviet Military Administration as its headquarters at the end of World War II. It was here that the second unconditional surrender was signed. Now the German-Russian Museum. Photo by Anagoria, distributed under CC BY-SA 3.0 license.  The first page of the Act of Military Surrender signed at Reims, France on May 7th. Note the date and time it goes into effect are handwritten. Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-49629-0002 / Nitsche / CC BY-SA 3.0 DE The first page of the Act of Military Surrender signed at Reims, France on May 7th. Note the date and time it goes into effect are handwritten. Bundesarchiv, Bild 183-49629-0002 / Nitsche / CC BY-SA 3.0 DE This month marks the 75th anniversary of the end of World War II in Europe. But on what date did the war end exactly? Was it May 8th 1945 – V-E Day in the United States? Or was it May 9th – Victory Day in Russia? In Germany, the end of the war is commemorated on May 8th. In fact, as a one-off for 2020, Berlin declared May 8th a holiday, in a way marking the culmination of a remarkable shift in the German collective memory. Over the course of more than seven decades, the country's capitulation has been transformed in the public imagination from “the German catastrophe” to a liberation from tyranny worthy of (sober) celebration: Germany's unconditional surrender put an end to a war in which tens of millions had lost their lives. Many were murdered by Germans in the name of the Nazi German regime, among them six million Jews, hundreds of thousands of Sinti and Roma, millions of Soviet prisoners of war, hundreds of thousands of people with mental disabilities, and thousands of homosexuals. Adolf Hitler committed suicide in his bunker in Berlin and the Soviet flag (likely) flew from the Reichstag on April 30th 1945, but even then, the war was not quite over. Hitler's designated successor as president of the Reich, Admiral Karl Dönitz, attempted to form some semblance of a government based out of the city of Flensburg on the Danish border. Dönitz tried negotiating with the Allies, hoping to bring German troops back from the east to prevent them from being taken prisoner by the Soviets. But by by the evening of May 6th 1945, the Supreme Commander of the Allied Expeditionary Force, Dwight D. Eisenhower, had had enough. He insisted that an unconditional surrender be signed immediately, otherwise Germany would face further bombing raids and troops fleeing the Soviets would not be permitted behind American lines. The surrender was to go into effect on May 8th at 11:01pm Central European Time. That would give the Germans just two days to try to get their troops back, but it was better than nothing. In 1944, the main Allies had agreed on a draft for the “Act of Military Surrender”: the surrender was to be unconditional and all power ceded to “Allied Representatives.” The US, UK, and USSR were also of one mind that German military officers should be the signatories – thereby pre-empting the creation of another “stab in the back” legend as after World War I, when senior military officials like Field Marshal Paul von Hindenburg had succeeded in convincing many Germans of the lie that their military had been undefeated on the battlefield and instead “stabbed in the back” at home. And so it was the Chief of the Operations Staff of the German Armed Forces High Command, General Alfred Jodl, who, summoned to Eisenhower's headquarters in the French cathedral city of Reims, signed the surrender ending the war at 2:41am local time on May 7th. American General Walter Bedell Smith and Soviet General Ivan Susloparov co-signed (and French General François Sevez witnessed) the document. There was only one problem. Joseph Stalin wasn't happy. The Soviet dictator had not given General Susloparov permission to sign the surrender. Also, the text didn't conform to the draft agreed by the Allies in 1944. These circumstances gave Stalin the excuse he needed to rectify the real deficiency of the Reims signing in his eyes: he hadn't choreographed it. He wanted representatives of all three branches of the German military, as well as Soviet Marshal Georgy Zhukov, to sign the surrender in Soviet-occupied Berlin, emphasizing the outsize contribution of the Red Army to the Allied victory over the Third Reich. This second signing ceremony was to take place at the headquarters of the Soviet Military Administration, located in the neighborhood of Karlshorst in southeastern Berlin. The German delegation was flown into Berlin from Flensburg on the morning of May 8th, but they were not taken to Karlshorst until late in the evening. There had been some delays. First, the Allied delegation had to make its way to Berlin, then they had to figure out who the signatories would be. Eisenhower (who could not be seen to have been summoned by Zhukov, his nominal subordinate) had sent his British deputy, Air Marshal Arthur Tedder, to sign in his place along with Zhukov. But General Jean de Lattre de Tassigny, a de Gaulle ally, insisted on signing on behalf of the French as well. The Soviets had not anticipated a French presence, and a French flag had to be improvised. More importantly, if only Zhukov, Tedder, and Tassigny signed, the Americans would be the only major Allied power to be excluded. The Soviets, however, insisted on limiting the number of Allied signatures to three. The compromise that was reached had Zhukov and Tedder sign on behalf of the Allies, and Tassigny and American General Carl Spaatz sign as witnesses. Minor alterations to the text – each revision had to be translated and each translation vetted – led to further delays. Consequently, the German delegation, comprising Field Marshal Wilhelm Keitel representing the German Army, Admiral Hans-Georg von Friedeburg of the Navy, and Luftwaffe General Hans-Jürgen Stumpff, only signed the surrender – after some dithering on the part of Keitel – sometime between midnight and 1am on May 9th local Berlin time. The document was backdated May 8th, and, in accordance with the Reims document (which was binding), the German surrender went into effect (retroactively) at 11:01pm on May 8th. Because of the one hour time difference, the surrender officially went into effect at just after midnight, May 9th Moscow time. More importantly, it was only on May 9th that the unconditional surrender was announced to the Soviet public – their Victory Day. This was not the case in the US or the UK. The signing ceremony at Reims had been packed with journalists and cameras; witnesses compare the experience to being on a movie set. But after the Soviets expressed their displeasure with the Reims document, Eisenhower issued a press embargo to allow time for the Soviets to conduct their ceremony in Berlin. Journalists were not permitted to file their reports until 3pm on May 8th, when Washington, London, Paris, and Moscow would simultaneously announce the surrender. The news leaked, however (36 hours being a long time to wait to report the end of World War II). Later in the day on May 7th, Associated Press reporter Edward Kennedy, believing the news was going to break after the capitulation had been mentioned on German radio, managed to get news of the surrender to London and from there to New York. It was 3:30pm in Paris, 9:30am in New York. That gave the newspapers plenty of time. The next day, May 8th, the New York Times front page headline read, “THE WAR IN EUROPE IS ENDED! SURRENDER IS UNCONDITIONAL; V-E WILL BE PROCLAIMED TODAY; OUR TROOPS IN OKINAWA GAIN.” With Americans and Brits celebrating on the streets of New York and London, both President Truman and Prime Minister Winston Churchill decided that they could not wait until the ceremony in Berlin was completed before declaring victory. At 3pm, Churchill intoned, “My dear friends, this is your hour.” At about the same time – 9am in Washington D.C. – Truman, using similar language, declared, “This is a solemn but glorious hour.” May 8th was V-E Day. But what was that “solemn but glorious hour” precisely? As we've established, Germany's unconditional surrender went into effect on May 8th at 11:01pm Berlin time. Since Germany had (re-)introduced daylight savings time (DST) in 1940, Berlin was two hours ahead of Greenwich Mean Time (GMT +2). It wouldn't be for long, by the way. On May 24th 1945, the Soviets, who remained the sole occupiers of the city until the summer, (temporarily) put Berlin on Moscow time (GMT +3). Time became a symbol of victory. It was a tool the Nazi German occupiers had wielded in France. In 1911, that country had adopted Greenwich Mean Time (GMT +0), implementing DST in the summers. When Germany invaded in 1940, Berlin time was introduced in the German-occupied north of France (GMT +2), while the time in Vichy France remained unchanged (GMT +1). In order to accommodate railway schedules, Vichy France put its clocks one hour ahead in the spring of 1941. Now all of Metropolitan France was on German time and it remained so even after its liberation in 1944 (and until today). France had decided to keep its clocks aligned with those of its British ally. In 1940, the UK had set its clocks ahead by one hour (daylight savings; GMT +1) and it did not turn them back in the fall. Instead, from 1941 the UK set its clocks ahead one hour further in the summers (GMT +2) to what became known as “British double summertime.” The object was to save fuel and to preserve the daylight for workers making their way home before blackout. It meant that London, Paris, and Berlin were all on the same time in the spring of 1945. Moscow was on summer time all year. In 1930, the Soviet Union had introduced so-called “decree time.” Clocks were permanently set one hour ahead of standard time (Greenwich Mean Time +3). The tongue-in-cheek term “decree time” implies the skepticism of a population still attuned to a diurnal rhythm: while the Soviet regime could “decree” what time it was, it could not actually affect when the sun reached its zenith. Farmers in the United States were similarly skeptical of daylight savings time. Soon after the attack on Pearl Harbor, a bill was introduced in the House of Representatives calling for year-round DST for the duration of the war. It was great for industry, but farmers were not amused: “I am distressed at the increasing degree of ignorance on the part of our urban population as to how their food is produced,” declared a New York congressman representing a rural district. Nonetheless, the bill passed overwhelmingly, putting Washington D.C. six hours behind London, Paris, and Berlin (GMT -4). When the law expired, the United States reverted to a chaotic system whereby towns and cities might choose to go on DST while the surrounding countryside did not. The “Act of Military Surrender” went into effect at 5:01pm on May 8th in Washington D.C.; 11:01pm on May 8th in London, Paris, and Berlin; and at 12:01am on May 9th in Moscow. To answer the question posed at the outset: the war ended on both May 8th and May 9th. That, however, is the conclusion of a pedant. It is more honest to acknowledge that the war ended on neither date. Although Germany's unconditional surrender was largely, though not entirely, adhered to, it is absurd to suggest the fighting ended with the snap of a finger. Hundreds of thousands were yet to die in Asia, where the war continued to rage. Europe, in turn, faced a redrawing of the political map and a refugee crisis of staggering proportions. Here, too, hundreds of thousands, if not millions, perished in the aftermath and as a consequence of the war. But in our various national collective memories, the day the war ended is, quite simply, the day we were told.  Corner of House B of the former "Abteilung Kiegsgefangenenwesen" Corner of House B of the former "Abteilung Kiegsgefangenenwesen" Over the last six to seven weeks (or has it been longer?), I have made a point of isolating myself physically as well as possible. The challenges one faces in this ongoing process are by now almost commonplace. With the dramatic decline of travel we are witnessing, guiding tours is, for the moment, a thing of the past. And yet: small, unexpected things bring me back to my “past life”. A friend pointed out a building I have cycled past on many occasions in our neighbourhood, saying it looked strikingly like a building of the National Socialist era. This was a good excuse to mount the iron horse once more and embark on a small fact-finding mission. Just a few blocks away from Rathaus Schöneberg – the town hall where John F. Kennedy once uttered his famous words Ich bin ein Berliner – stands the Berlin School of Economics and Law. While the upper parts of its buildings clearly have been rebuilt, the bullet holes on the outside walls of the ground floor clearly indicated that this had been constructed before the Second World War. Originally constructed for the Reich Economic Chamber in 1939, today's House B became home the Supreme Command of the Wehrmacht the following year. The German Army housed its Abteilung Kriegsgefangenenwesen (Department for Prisoner of War Affairs). The rules and regulations for treatment of prisoners-of-war (POW) were determined here. As one can imagine, these varied according to the nationality of the prisoner in question. A Russian POW, for example, would have been deemed belonging to the Slavic ‘race’ and therefore sub-human, whereas a different set of rules would have been applied to a French, British or United States POW. This reminded me of an issue that is often raised on my concentration camp memorial tours of Sachsenhausen. Located north of Berlin in the town of Oranienburg, Sachsenhausen was more than a concentration camp during the Third Reich. Among the adjacent facilities was the Inspectorate of the Concentration Camps, which coordinated the entire camp system on German and German-occupied territory. It had moved from Berlin to Oranienburg – the city in which Sachsenhausen stands – in 1938. One finds houses that had been built for camp guards and members of the SS (the elite paramilitary unit of the National Socialist Party in charge of the camp system after 1934) on the street leading to this building. In spite of efforts by the former director of the memorial, these houses are still privately held. After a long and intense visit to the memorial, visitors often ask how one can live in places like these. This is an understandable question to which, having grown up and lived in Germany, I sometimes offer a simple answer: if you want to avoid living in a place tainted by the National Socialist past, Germany is not it. There is a little more to this. The past is something one cannot escape, especially when it comes to dictatorship, global war and genocide in the twentieth century. There was no way for German society to avoid the legal, economic and political consequences if it wanted to re-establish itself in the world. The question is how one deals with that past – once you come around to it – and it is answered differently from generation to generation. In our day and age the past actions of the regime are still owned by places like these. While the Sachsenhausen memorial serves a civic and educational function, the Berlin School of Economics and Law does not eschew the past of its facilities either. Its website provides a history of the building and this informs its commitment to learning and cultural diversity, even though it does not offer degrees in History. At a time when there are fewer of those who suffered in the camps alive today, transferring the lessons of the past to a younger generation, which can learn how to make the best of our crisis-ridden world, is vital for our future as a society. Posted by Torben  This late 19th century monument to Albert the Bear shows him as a crusader bringing the true faith to the pagan Slavic peoples of Brandenburg. It's in the Spandau Citadel. Photo by Lienhard Schulz, distributed under CC BY-SA 3.0 license. This late 19th century monument to Albert the Bear shows him as a crusader bringing the true faith to the pagan Slavic peoples of Brandenburg. It's in the Spandau Citadel. Photo by Lienhard Schulz, distributed under CC BY-SA 3.0 license. The Slavic prince Jacza of Köpenick had been defeated in battle and was on the run, with Albert the Bear and his Saxon German followers in hot pursuit. They drove him to the banks of the Havel River at modern-day Gatow in western Berlin. Jacza's only option was to ride out into the water or face certain slaughter. The river, however, was deep, and slowly pulled Jacza and his horse under. He prayed to Triglav, one of the gods of his people, to come to his aid. Nothing. In his desperation, he turned to the Christian God of his enemies. Immediately, as if by an invisible hand, he and his horse were drawn from the current. Jacza, safe on the opposite river bank, hung his shield on a tree and made a solemn vow to be baptized. It was the 11th of July 1157. Thus the pulp version of the legend of the founding of the margraviate of Brandenburg, the territory of which Berlin would eventually become the capital. It neatly encapsulates the early history of this region, while sugar-coating the brutal treatment of its Slavic inhabitants at the hands of German colonizers. Nobles like Albert the Bear saw an opportunity for territorial expansion in Brandenburg, parts of which had already seen the establishment of bishoprics and been temporarily absorbed into Germany in the 10th century. The justification for war was religious; the invasion of Slavic lands was explicitly framed as a crusade. After the defeat of Jacza, the leader of one of the Slavic tribes in Brandenburg (the Sprewanen), Albert and his (German) successors were able to exert permanent political control over Brandenburg and colonize the land with farmers, craftsmen, and merchants – mainly from western Germany. The Slavic communities faced slaughter, subjugation, or assimiliation. Everyone became Christian. Brandenburg, though a poor backwater for many centuries, became the core of a political unit that, in the guise of Prussia, would dominate the whole of Germany and much of Europe in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. In 1845, the Prussian king and inveterate romantic Frederick William IV commissioned the architect Friedrich August Stüler to create a monument to Jacza's conversion. After partial destruction in World War II, it again stands in Berlin's Grunewald Forest on the small Schildhorn peninsula where Jacza allegedly hung up his shield (Schild) for good. Posted by Torben  It's hard to make out, but the plaque at the base of the monument reads, "1939-1945." It's hard to make out, but the plaque at the base of the monument reads, "1939-1945." In better times, I made it a habit on my frequent trips to Munich to visit one of the many beautiful small towns in the surrounding Bavarian countryside. One such side trip took me to Burghausen, a town nestled, like Salzburg, in the valley of the Salzach river, with a commanding castle straddling the ridge above. If you visit, maybe during the notable Jazz festival in March, be sure to cross the river (into Austria; the river marks the border) and climb up the hill opposite the town. You will be able to take in the whole of Burghausen and the full expanse of its castle. This takes some doing: the castle is 3,448 feet long and is listed in the Guinness Book of World Records as the longest in the world. However, if you go onto the castle's website, you won't see a banner headline touting the world record. Instead, tucked within a lengthy historical description, it is demurely mentioned that “Burghausen Castle, which has a length of over 1,000 metres, is one of the longest castle complexes in the world.” As a German citizen who grew up in the United States but who has lived in Europe for twenty years, I have reconciled myself (sometimes I think: resigned myself) to being fully assimilated into German society. But every now and again I feel a twitch of my American upbringing; some negligible occurrence will strike a dissonant note that reminds me that I can't fully shed my cultural apartness. And that was the feeling I had after walking a full two-thirds of a mile from one end of the damn castle to the other only to be told in the museum shop brochure that the castle is indeed quite long and that the “Guinness Book of World Records even claims it is the longest castle anywhere.” Claims? You've got the longest castle in the world – the Guinness Book of World Records says so – and you want to quibble? This was wrong. This was offensive. This was downright un-American. I though of this recently after watching German chancellor Angela Merkel deliver an unprecedented televised address about the Corona crisis. Apart from the traditional – and traditionally anodyne – televised new year's speeches our chancellors are expected to give, this was the first time Merkel had chosen this mode of communication in all her nearly fifteen years in office. Here's the part of the address that was most frequently quoted in German media: I turn to you today in this unusual way because I want to tell you what guides me as chancellor and all my colleagues in the federal government in this situation. This is part and parcel of an open democracy: that we also make political decisions transparent and explain them; that we justify and communicate our actions as well as possible so that they are comprehensible. I firmly believe that we will succeed in this task if all citizens see it as their task. So let me say that this is serious. Take it seriously too. Since German reunification, no, since the Second World War, there has not been a challenge to our country that depends so much on our joint solidarity. Not exactly soaring rhetoric. Merkel's tone, even while she resorts to a, for her, highly unusual historical analogy to emphasize the severity of the crisis, remains largely sober, matter-of-fact. For a Merkel speech, however, this was a barn-burner: “We have rarely seen the chancellor speak with as much pathos as she did in her televised address,” read a column in one of the country's leading newspapers, the Süddeutsche Zeitung. In part, this has to do with Merkel specifically. She is not a gifted public speaker and has tried to turn that weakness into a strength, cultivating the image of a pragmatic doer who doesn't waste her time on empty talk. But it's not just her. Before Gustav Heinemann was elected West Germany's president in 1969, he was asked if he loved the Federal Republic whose head of state he was soon to become. He answered, “Oh please, I don't love states, I love my wife; that's it.” We are not used to our politicians stirring the heart-strings or appealing to our patriotism. We tend to be supremely skeptical of superlatives. And we certainly do not couch our response to political challenges in the language of war. Donald Trump has called himself a “wartime president” in the face of the Corona crisis; the British “war cabinet” meets daily to discuss its response to the pandemic; French president Emmanuel Macron has declared that “we're at war” against the virus. Merkel, though she tells us we haven't faced a challenge of this magnitude since 1945, does not suggest the current challenge is like a war. Of course, there are good reasons why she wouldn't do that. The United States, the UK, and France are rightly proud of their role in what Studs Terkel called “the good war” against an evil, genocidal enemy. It is the hard-won awareness that we were indeed that evil, genocidal enemy that goes some way in explaining the reluctance of German politicians to use martial rhetoric. And more than that: for good reasons we do not have the avenues open to other countries to commemorate the war and the war dead. To be sure, we have a national memorial for the murdered Jews of Europe and many more memorials across the country reminding us of the horrors of the Holocaust. We also have a memorial commemorating “all victims of war and tyranny.” But we don't have a Veterans' Day, we don't have a Memorial Day, we don't have an Imperial War Museum or memorials to the German soldiers who died in World War II. Those soldiers are certainly remembered – within the family and the community from which they hailed. Local World War I memorials will often have the dates “1939-1945” added to them to allow for such remembrance, obviating the need for separate (and inevitably problematic) World War II equivalents. We can't describe ourselves as the biggest or the best. We tried that and the results were disastrous. Germany's is a political culture trying to escape its exceptionalism, because that exceptionalism (let's leave a more nuanced historical discussion aside for a moment) led to Auschwitz. Germany is a country that doesn't want to be special; it's a country that, sometimes desperately, wants to be like everybody else. But as Heinemann's “I love my wife” answer suggests, the sobriety of our public and political discourse goes beyond an effort to eschew the language of war. Overt displays of patriotism are generally frowned upon, as are sentimentality and pathos and exaggeration. This is true for political speeches, it's true for newspapers and the TV news, and it's true for weather reports. In Germany, we have snowstorms, not snowmageddons, snowpocalypses, snowzillas, or any of the other delightful meteorological portmanteaus a cursory Google search turns up. When a plane crashes or people are displaced from their homes by river floods, evening news programs will focus on the facts and figures, not on the emotional impact of the tragedy, not on the loss. Perhaps this too has to do with the experience of the Nazi period and the Second World War. In 1967, the psychoanalysts Margarete and Alexander Mitscherlich published a famous study called The Inability to Mourn. In it, the authors suggest that postwar West German society was deeply informed by the loss many Germans felt at the defeat of the Third Reich. This was a regime that people had been emotionally invested in. As perverse as it seems, its collapse was experienced by many as a betrayal of a promise. And this loss, this betrayal, could not be mourned after the war in the face of a burgeoning acceptance (or at least the expectation of acceptance) that this regime was deeply evil. In short, the Mitscherlichs argued that Germans felt the need to mourn Hitler but couldn't. And how did they cope with this inability to mourn? They focused on rebuilding the country, on economic recovery. They gave precedence to the material over the spiritual. Most contemporary scholars do not give much credence to the Mitscherlichs' analysis. But when their book was published, it clearly touched a nerve. There is a price we pay for banishing pathos and emotion from the public square, for our lack of a civil religion. A news report that doesn't address the horror of a plane crash or a flood or a pandemic just isn't commensurate with what we're feeling in a moment of uncertainty or loss. We may long at those times for our political leaders to signal to us – not just on an intellectual, but on an emotional level – that we're all in this together. But then, it seems, we don't always know how. When pathos does venture into the public realm in Germany, the result is often awkward or it devolves into kitsch – at least from the perspective of non-Germans. If you ever watch the movie The Miracle of Bern about Germany's first soccer World Cup championship in 1954, you'll be forgiven for thinking that even the Hallmark Channel would have given it a pass. But the former chancellor Gerhard Schröder admits to having wept as he watched the dramatic depiction of underdog West Germany defeating mighty Hungary in the final. That a 21st century movie celebrating a German triumph would look to a soccer tournament is no accident. Soccer is one area where over-the-top emotion, irrational exuberance, and patriotism can all come together. It has become a tradition to fly the German flag from cars and balconies when a major tournament involving the national team is going on. The chants at games are often wannabe poetic: “We'll go anywhere – just not home” or “We haven't seen anything as beautiful in a long, long time.” (Remarkably, they're pithier in German.) And when it comes to chants supporting your local club, exceptionalism, not to mention chauvinistic bravado, is encouraged: “Everyone but Frankfurt is shit.” (This, by the way, happens to be true.) Soccer is the exception – albeit perhaps not entirely. Germans are, of course, attuned to American politics and American pop culture. And it rubs off. We now have presidential style debates between our candidates for chancellor, although the less-than-stellar production values and weedsy policy questions don't exactly make for riveting television. Germany produces a seemingly never-ending stream of overwrought made-for-TV romances and tear-jerkers, although often they are set in places outside of Germany that are considered more romantic, like Italy or Ireland. We also have a tabloid newspaper culture that isn't known for its reserve. After Joseph Ratzinger was elected Pope Benedict XVI, the headline in the Bild-Zeitung famously read, “We're the Pope!” And while the foundation that is responsible for the castle in Burghausen is reluctant to lay claim to its world record status, the town of Burghausen plasters “world's longest castle” on anything it can. In short, we should be very reluctant to present cultural or political norms as immutable – or the product of something as dubious as a “national character.” Instead, they are – in Germany as anywhere – complicated, ever-changing, and ambivalent. But whatever the reasons for the sobriety of our public discourse, in times of Corona, it can be comforting to have political leaders present relevant facts in a straightforward way. And to know that, in order to communicate the gravity of the current situation, they need not resort to superlatives, war metaphors, or pomp and circumstance. They can just tell us. Posted by Torben If you visit the Invalidenfriedhof cemetery in central Berlin, you will find not the grave but the gravestone of the most famous fighter pilot of World War I, Manfred von Richthofen. The “Red Baron,” who was so memorably pursued by Snoopy in Peanuts cartoons, is credited with more air combat victories than any other pilot of the war. Richthofen was killed in the spring of 1918 over France, where he was buried with full military honors by the British. After the war, he was reinterred at a military cemetery, also in France. His remains were brought to Berlin in 1925. The massive gravestone on which is written, laconically, only the name “Richthofen,” was placed at the gravesite in 1937 at the behest of Nazi Air Minister (and fellow World War I fighter pilot) Hermann Göring; the Nazis considered the original headstone to be too modest.