Paragraph. Zur Bearbeitung hier klicken.

Paragraph. Zur Bearbeitung hier klicken.

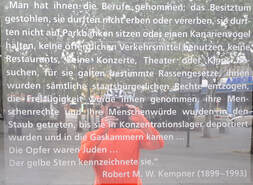

Mirror, Mirror on the Wall ... What the Spiegelwand Memorial Tells Us about Holocaust Remembrance5/29/2020  Posted by Carlos Foreign visitors on our tours of Berlin often praise Germany for commemorating the victims of National Socialism. While the Memorial to the Murdered Jews of Europe (the Holocaust Memorial) in the city-centre is a frequent stop, I only once had the opportunity to take a family to the Spiegelwand memorial in the southern neighbourhood of Steglitz. Spiegelwand literally means ‘mirrored wall’. It is also a testament to the local tensions that underlies Germany’s acknowledgement of the Holocaust or Shoah as a nation. Wolfgang Göschel, Joachim von Rosenberg and Hans-Norbert Burkert designed a very special memorial in the 1990s. Unveiled ten years before the Holocaust Memorial, the Spiegelwand is a 9 metre high and 3.5 metre wide set of glass plates. These bear the names, dates of birth and addresses of 1,723 Jews who were deported and murdered. This monument is informed by surviving deportation lists of Jews from Steglitz and nearby areas. In this way, the victims can be honoured as individuals with a name, a history and a home. This is expressed in a quote of Robert Kempner, a Jewish resident of Steglitz and later plaintiff at the Nuremberg Trials. It adorns the Spiegelwand and can be loosely translated as follows: "One took their jobs, stole their possessions, they were not permitted to inherit or bequeath, they were not allowed to sit on park benches or keep a canary bird, to use public transport, to visit any restaurants, any concerts, any theatres or any cinemas, certain racial laws were applied to them, all civic rights were withdrawn from them, the right of free movement was taken away from them, their human rights and their human dignity was kicked into the dust, until they were deported into the concentration camps and came into the gas chambers ... The victims were Jews ... The yellow star marked them". And yet there is an almost inherent ambivalence to the memorial. To be sure, its location on Hermann-Ehlers-Platz, a central meeting place and home to a poplar market in downtown Steglitz, is appropriate. The memorial effectively points to the building that once served as a synagogue; however, the Spiegelwand is not immediately visible, nor is the former synagogue, when coming to the square from the main street. From a purely solipsistic or self-centred perspective, it is impracticable to show this to visitors with limited time to see Berlin. The Spiegelwand is literally out of the way. This is a lens through which one can view the heated debates over the memorial that consumed the parliament of Steglitz for years. The conservative CDU, the (economically) liberal FDP and the rightwing Republicans of Germany held a majority and opposed the design of the Spiegelwand. Among the many reasons they laboured was the concern that owing to its size the memorial could be besmirched by Neo-Nazis. To someone reading about the topic in hindsight, this is somewhat odd. The German Republicans have been known for their hard right sympathies; were they, out of respect for the victims and their families, pleading guilty to potentially vandalising a Holocaust memorial? As the controversy assumed grotesque dimensions in which almost every inch was negotiated, Berlin’s Social Democratic Minister for Construction and Housing Wolfgang Nagel intervened. The reputation of Berlin had begun to suffer. Looking back, this debate is strange only at first sight. Germany was confronted with a number of challenges as a reunified society in the early 1990s. Two different forms of commemoration of the National Socialist past had to be reconciled; concentration camp memorials, especially those in the former East Germany, were now redesigned; Neo-Nazism was on the rise; debates about the national Holocaust Memorial were taking place; and a travelling exhibition about the crimes of the regular German Army or Wehrmacht, hitherto seen as an honourable counterpart to the murderous SS during the Second World War, was making the rounds. Bearing responsibility for the guilt of the parent generation arguably was particularly hard for conservative Germans. Social Democrats, Communists and others whose political, religious, cultural or sexual identity had a history of persecution under National Socialism had something to protest against when dealing with the Third Reich. By contrast, it had been conservative and self-styled independent politicians led by Chancellor Franz von Papen who had convinced President Paul von Hindenburg to appoint Adolf Hitler Chancellor on 30 January 1933. The democratic credentials of the military officers and civilians behind the failed coup of 20 July 1944 – and often celebrated in conservative circles – were being viewed critically by the 1990s. It was hard to avoid confronting the simple truth that there was no excuse for Hitler and genocide. This feeling of guilt can be less a question of political conviction than of an unfinished process. As a native German speaker, I have found myself conversing in two worlds when showing my beloved city to English speakers. On the one hand, customers eager to learn about the Third Reich and to understand what lessons can be drawn for their own present have emphasised what a role model Germany and its memorials are to the rest of the world. On the other, drivers have told me in German that they are enervated by foreign visitors just wanting to see Third Reich sites as though Germany had nothing more progressive to offer and the rest of the world nothing but contempt for Germans. The irony is tangible as the significance of commemoration is almost lost in translation. The ambivalence the Spiegelwand can remind us of is not without merit. This local memorial underlies the national intent behind the Holocaust Memorial: the German state is at pains to show that the Germany of today is a different one to the National Socialist state and that it unequivocally bears responsibility for those whom it had persecuted and murdered. This Germany which wishes to learn from its shameful past is the ideal I find visitors admiring. The existence of these memorials shows that as a society Germany has come a long way. The debates at both the political level and in day to day conversations reveal that there still is a road that lies ahead. Not only should it be embraced, but with hope and optimism as well.

2 Comments

Ray Clifford

11/27/2020 05:54:29 am

Was very moved to "discover" this memorial to the local jewish people, the names, address, date when they were taken to their fate in the gas chambers.

Reply

2/22/2023 02:27:05 pm

I wanted to express my gratitude for your insightful and engaging article. Your writing is clear and easy to follow, and I appreciated the way you presented your ideas in a thoughtful and organized manner. Your analysis was both thought-provoking and well-researched, and I enjoyed the real-life examples you used to illustrate your points. Your article has provided me with a fresh perspective on the subject matter and has inspired me to think more deeply about this topic.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

|

|

Copyright 2016

|